AKA, a respectable and venerable American faith tradition

As a minister, the question I get asked most often is also rather straightforward: “What is Unitarian Universalism?” And I have to admit that, it’s a fair question. It’s also somewhat more neutral than, “Is that a cult?” Whatever else Unitarian Universalism is, it is and apparently remains “the best kept secret in town.” No wonder there’s some confusion!

Recently, a colleague wrote that the UU church she served had just received a Yelp review from an Evangelical Christian. I’m not sure how many folks are using Yelp to rate churches, or whether this “reviewer” is in a position to offer any helpful advice to a would-be seeker, but I will say that I very much appreciated their conclusion: that our church is, quote, “a house of blasphemy and deceit.” If I ever write a book about Unitarian Universalism, that will be the title.

Obviously, Unitarian Universalism is different from Evangelical Christianity — and it’s about as far from religious fundamentalism as you can get and still be in the same conversation. But the Yelp critic is particularly ironic since, it turns out, that the last person who actually did jail time for blasphemy in the USA just happened to be a Unitarian!

There is, has been, and will likely remain, confusion about who we are and whether we are a “real religion”. When 20% of Americans identify as Catholic and another 40% or so claim membership in one Protestant Christian denomination or another, it’s pretty easy to loose track of a faith tradition whose total US-based membership gets lost as a rounding error. Assuming my calculator is being appropriately used, my estimates put us at about point-oh-five percent of the current population, or thereabouts. In raw numbers, we have a bit over 1,000 churches and a bit under 150,000 members here in the USA; there are about 800,000 people worldwide, who, while perhaps not active members, still check our box on forms. We’re small, but scrappy.

But, to be clear: while Unitarian Universalism, as a combined denomination, only dates to the early 1960s, both Unitarianism and Universalism are historical, well-documented faith traditions, and each are at least as old as the United States — and yes, for the record, both most definitely did spring out of (Protestant) Christianity.

And at this point however, let me refer you once again to the title of my not-yet published book, above. Because “spring out of” does not mean “equivalent to”. So, if you have been told that the words ‘faith tradition’ means “bound by a common dogma, doctrine, or creed”, and if deviations from that definition cause spontaneous sputterings that include the word ‘blasphemy’, well, Unitarian Universalism may make your keyboard itch. Because UU folks do deviate.

Who we are, and what we believe, is a bit complicated, but one of the most concise answers I’ve heard is that Unitarian Universalism is a non-creedal, liberal, religious tradition that celebrates diversity of thought, background, identity, belief, and purpose. But perhaps it would just be simpler to say that Unitarian Universalism is many things — by history, by design, and by aspiration.

Today, there are a great many individual UU’s that call themselves Christian, just as there are UU churches that celebrate traditional Christian liturgies and, yes, even some that offer the Eucharist as part of their worship services. However, the point worth underlining here is that visitors (and members) should at the very least expect some variety in religious expression among the individual congregations that find a home under the umbrella of Unitarian Universalism. Every UU community is just a little different. Some do lean Christian. Many do not.

If that’s confusing, perhaps it would help to say that Christianity is very definitely one of the Sources that UU’s draw from, but is only one of six such Sources (see below). Another way I’ve heard it said is that Unitarian Universalism is more like “Christianity Plus”, or maybe that it includes a “superset” of Christian beliefs, practices, and goals. Or perhaps it would be helpful to say that most UU’s do not “center” Christ — Jesus of Nazareth is one of many figures whose words of inspiration can find voice in a UU church, congregation, fellowship, or society on any given Sunday morning.

There was a symbol that was used by a Universalist group called the Humiliati that might help understand this relationship: the circle with an off-center cross. While the Cross is certainly present, the point is that there is more room in that circle for a wider Truth. You can also see this idea of “wider truth” celebrated today in the more modern UU chalice, the symbol at the bottom of this page.

Another way of imagining our theological relationships comes from the Rev. Dr. Forrest Church, who talked about “The Cathedral of the World“. He says that there are many windows in “The Cathedral”, each with its own view on Truth, each window creating its own pool of light. “But the windows are not the light. They are where the light shines through.” Each of the many religious traditions in the history of our world, then, could be imagined as individual windows. And if that is so, then perhaps we can say that UUs are those who are moved by the light of many different windows.

The image I tend to use for today’s UU faith is that of a “big tent”. I like to believe that there is room under our tent for a wide range of views and beliefs, and I believe that the quality of the conversation under that tent rises as the diversity of opinion increases.

So, in a UU congregation, you can find Christians holding to the word and life of Christ. You’ll also find Reformed Jews, Western Buddhists, Humanists, Pagans, those that call themselves “spiritual, but not religious”, and those that simply are NONES. In short, what you’ll find is diversity, curiosity, and a mandate to wonder. Add to that a rather robust suspicion for authority and a categorical rejection of what sometimes gets called “blind faith”, and what you’ll likely find on any given Sunday, in any given UU church, is the opposite of “cult”.

What UU’s agree on, what ties us together as a community, are Seven Principles.

The Seven Principles

UU’s have no Shahada, no Shema, no Apostle’s Creed, no confession of faith. Instead:

Unitarian Universalism affirms and promotes seven Principles, grounded in the humanistic teachings of the world’s religions. Our spirituality is unbounded and draws from scripture and science, nature and philosophy, personal experience and ancient tradition as described in our six Sources.

Those Principles that UU’s “affirm and promote” are:

- 1st Principle: The inherent worth and dignity of every person;

- 2nd Principle: Justice, equity and compassion in human relations;

- 3rd Principle: Acceptance of one another and encouragement to spiritual growth in our congregations;

- 4th Principle: A free and responsible search for truth and meaning;

- 5th Principle: The right of conscience and the use of the democratic process within our congregations and in society at large;

- 6th Principle: The goal of world community with peace, liberty, and justice for all;

- 7th Principle: Respect for the interdependent web of all existence of which we are a part.

Our Six Sources

By my count, there are three streams that flow into the river that is today’s UU: Unitarianism, Universalism, and Religious Humanism.

It’s worth noting that Unitarianism and Universalism as ideas were not unique to history or to the United States. UU historians are quick to point out inspiration in the heresies of Arianism, Pelagianism, and others, back to the very beginning of Christianity. They also note the development of Unitarianism in Eastern Europe, like the Unitarian Church of Transylvania, which dates back to the 16th century. As interesting and suggestive that these links are, however, they’re at best parallel lines of development. Unitarianism and Universalism, as they became threads of the eventual merger, are both distinctly American.

At the time of the merger in 1961, Universalism was expressly Christian, and preached the gospel of Universal Love and Salvation–their goal, you might say, was to “Love the Hell out of the World.” The founding of Universalist church in the USA is attributed to the arrival of John Murray in the late 18th century, after both he and his religion were hounded out of England. Over the course of the 19th century, and under the hand of its most celebrated evangelist, Hosea Ballou, Universalism became one of the largest and fastest-growing denominations in the rapidly expanding nation. I believe that the reason Universalism declined in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was entirely due to it’s success–by WWI, the idea of “eternal Hell” had fallen largely out of favor in most mainline church pulpits (that is, until Fundamentalism came to the US in the early 20th century, but that’s a different story).

Unitarianism certainly started as expressly Christian. It got its start in the 17-18th century, and in a startling echo to the Universalist story, it came to America as the result of yet another Englishman fleeing a mob — in this case, one Joseph Priestly. Not quite a generation after Priestly’s “relocation”, upstarts William Ellery Channing (and a few other New England preachers), caused a stir in the newspapers of the day. Using the latest Enlightenment research and practices, they vigorously and publicly called into question the Calvinist orthodoxy of the Puritan North, and concluded (among other things) that the traditional Christian teachings of the Holy Trinity, Original Sin, and human depravity had no Biblical foundation or support. These arguments were not received well, and the upstarts were accused of all manner of terrible things — blasphemy, deceit, and perhaps worst of all, Unitarianism. I suppose that it is not surprising that those upstarts simply claimed the name.

Over the 19th century, and with the work of prominent Unitarians like Ralph Waldo Emerson, Margaret Fuller, and Henry David Thoreau, Unitarianism evolved rather profoundly. Transcendentalism, Humanism, and Naturalism are all threaded through the tapestry of Unitarianism, right alongside Eastern mysticism — some of the very first translations of Eastern philosophy were done by Unitarian Transcendentalists. It’s not wrong to say that these threads led to Spiritualism, Theosophy, Christian Science, the Unity Church, and the so-called “prosperity gospel” (can’t win them all).

After Unitarianism and Universalism, Humanism is the third major wellspring of inspiration within today’s UU. Today, when someone says “Humanism”, they typically mean “Secular Humanism“, a vocal opponent to religious fundamentalism, but Humanism, as a religious movement, had roots in the Enlightenment. In the late 19th century, the movement had woven the ideals of reason, truth, and logic directly into the fabric of community and social engagement. There, the Free Religious Association, the Freethinkers, and other groups, explored the edges of this new “religion” at a time when industry and society was evolving as rapidly as scientific understanding. In 1933, a group of influential academics and preachers (many of them Unitarians) signed the first “Humanist Manifesto“, a declaration of Good Without God, a way to form a more perfect union without metaphysics and supernaturalism, one instead grounded in science, tolerance, and human capacity.

What all this means is that there is no one book of holy scripture in today’s UU churches; while the Bible is no longer “centered” as the sole source of Truth and Divine inspiration, it is widely revered. To that richness, today’s UU’s find inspiration from many sources — six of them, to be exact — and together with the Principles, they create the shape of “the big tent”.

- Direct experience of that transcending mystery and wonder, affirmed in all cultures, which moves us to a renewal of the spirit and an openness to the forces which create and uphold life;

- Words and deeds of prophetic people which challenge us to confront powers and structures of evil with justice, compassion, and the transforming power of love;

- Wisdom from the world’s religions which inspires us in our ethical and spiritual life;

- Jewish and Christian teachings which call us to respond to God’s love by loving our neighbors as ourselves;

- Humanist teachings which counsel us to heed the guidance of reason and the results of science, and warn us against idolatries of the mind and spirit;

- Spiritual teachings of Earth-centered traditions which celebrate the sacred circle of life and instruct us to live in harmony with the rhythms of nature.

The last major revision to the Seven Principles and Six Sources was in the mid-1980s. Perhaps a testament to the enduring power of their poetry and elegance, they have remained largely untouched in the years since. It’s important to understand that this resilience was not expected — the UUA Bylaws include provisions for periodic updates (every 15 years) under the expectation that a movement like ours could benefit greatly from a reimagining and realigning to the changing times we UUs might find ourselves in.

Six Shared Values — a 2024 revision, an update, and a reimagining

After a very turbulent decade (Black Lives Matter, the first Trump administration, #MeToo, the resignation of the UUA president Peter Morales, and a global pandemic), the Unitarian Universalist General Assembly chose to meet the moment. And so it was that in 2024, our congregational delegates voted overwhelmingly to adopt a sweeping set of revisions to our Principles and Sources.

What replaces them are a set of Six Shared Values. To be candid, it is unclear that the revisions as adopted are an improvement (the language alternates between obtuse and abstruse), but that’s all water under the bridge.

The Shared Values are as follows (in the order presented by the UUA), and include my (still evolving as of the Winter of 2024) personal thoughts and best attempts to constructively make sense of them.

Interdependence. We honor the interdependent web of all existence and acknowledge our place in it.

Much like the old Seventh Principle above, this value invokes the Bodhisattva ideal that “all of us need all of us to make it”, or if you’d prefer a more Christian formulation, that “salvation (if any is on offer) can only ever be a communal enterprise” — just like identity, meaning, love, and hope are also only the product of community. I like to say that this neatly parallels the South African concept of ubuntu. But you might also say, instead, that humanity is an interlinked and an integral part of nature and not separate from nature, just as nature is an interlinked and an integral part of humanity and not separate from humanity. Again, those with Buddhist leanings might recognize this as the co-dependent co-arising of all things. “No one stands alone,” and, “No man is an island,” would also be in line here. All of that said, the basic idea worth holding to is rather simple — people need other people, and while people, relationship, and community can be (and often is) messy and problematic, our faith reminds us that the community is at least as important as the individual. That’s why we aspire to something we can call “beloved”.

Pluralism. We are all sacred beings, diverse in culture, experience, and theology.

Pluralism is the only place where Unitarian Universalist theology explicitly separates from other liberal faith traditions. That is, all of the special things we say about our (other) values, virtues, principles, and aspirations, all are echoed and fully articulated by a great many other faith traditions. When you get past the privileged words, special phrasing, and tradition-specific stories that those traditions prefer to couch those values, virtues, principles, and aspirations, I find that the ground covered is pretty common and well-trodden. Except for this “pluralism” thing. Because not only do Unitarian Universalists accept that there are “many paths” on the journey to wisdom, meaning, salvation, heaven, or whatever our purpose (or telos) is here in the world, UUs simultaneously affirm and promote a great many of those paths as being not just “okay”, but valid, good, righteous, appropriate, healthy, and divine — and none are particularly privileged or centered. “Many paths, one church.” Good UUs can be found with many different ideals, virtues, values, and spiritual practices — there are Christian UUs, Jewish UUs, Muslim UUs, Buddhist UUs, Hindu UUs, Humanist UUs, Pagan UUs, Atheist UUs, and quite a bit more besides … and all of that is totally okay with us because we don’t have to think alike to love alike. And that level of explicit flexibility, acceptance, and understanding is, as far as I know, unique.

Justice. We work to be diverse multicultural Beloved Communities where all feel welcome and can thrive.

It’s said that our faith does not stand on tradition, it moves — always seeking to bend the arc of history toward freedom, liberation, and human flourishing for all human beings. If UUs are anything, it’s this: we have no tolerance for intolerance. For the record, this is where Liberation Theology enters the chat. Now, our seminaries have spilled oceans of ink on the topic of justice, social action, and activism, so I won’t do more here except to note that our history of engagement is robust, from John Brown anti-slavery insurrections to Jewish exfiltrations during World War II to martyrdom during the Civil Rights movement. I think the only thing I might add to that enthusiasm is perhaps more of a wondering (and a warning?), especially for the activist. That is, I wonder if what some of us center is not justice, but injustice. Justice is a good and positive state. Injustice is … something else. And if that’s all that fills the mind and consumes the heart, well, you are what you eat. Personally, I believe that justice-work can and should be part of a larger whole — for a person, a community, or a movement, but most especially, for a church. But social justice — or, perhaps more specifically, social action, where the focus is on practical goodness for your community and its neighbors — is but one guiding star held within a constellation of others (and in this particular case, it’s one of Six).

Transformation. We adapt to the changing world.

Another call-back to the Seven Principles, this one (at its best) invokes both the old Third and Fourth — acceptance and growth, seeking truth and meaning. I’m reminded of the saying from Maya Angelou: “Do the best you can until you know better. Then when you know better, do better.” The emphasis is on doing and not just knowing, because thinking our way into a better world seems a lot harder than actually making the world better. We are called to lend our hands to change. Following Octavia Butler, the only eternal truth is change — and the truth that change can be shaped. In ourselves. In the world we find ourselves in. We have the power and the responsibility to shape possibility and ultimacy. But perhaps we could say it this way: “We are not meant to be, but to become — and we are always becoming.” And the more we know, the more we can do. Once upon a time, this might have been called “salvation by character”, where ‘character’ was something one could and should cultivate (like a garden) through continual practice, education, and accountability (because testing ideas in the area of communal life is how we gather wisdom and not conspiracy theories). This is the reason why adult RE gets offered.

Generosity. We cultivate a spirit of gratitude and hope.

This feels like a casual-dress version of the Aristotelean virtue of “magnanimity” (which is admittedly a mouthful), and I want this connection to be true because there has to be more than enshrining pledge gifts or the blandly enervating “cultivation of a spirit of gratitude and hope”. Instead, I want to say that making generosity a shared value perhaps ought to invoke something more familiar to our Jewish friends and family: tikkun olam, our collective human obligation “to repair the world”. That is, we humans are generous because it is our highest aspirational purpose to serve, and whether our giving is time, talent, or treasure, our gifts are best offered up to make the world a better, kinder, more loving place. Toward positive change. To creating Beloved Community, the city on a hill, Heaven on Earth (and not just after). Our Social Gospel ancestors might have agreed with this, emphasizing that Heaven was never some other-where, it was always supposed to be here on Earth — and it could yet be, if only we chose to make it so. The philosopher Peter Singer might invite us to see altruism and giving as our defining human characteristics, and that we moderns should consider “effective altruism” as the ethic our world needs. Our more Buddhist colleagues might recognize generosity as the act of letting go (of attachments), that firm first step on the path to personal (and community) enlightenment. Generosity is a lot of things, but it ought to be at least be the root of our desire to act for peace and justice and human flourishing.

Equity. We declare that every person is inherently worthy and has the right to flourish with dignity, love, and compassion.

Once upon a time, this could have been our First Principle — that “we affirm and promote the inherent worth and dignity of every person”, a Principle which was a deliberate and explicit rejection of the vile and destructive (and yet wildly popular) doctrines of Original Sin and human depravity. That is, it was less a defiance of injustice than it was about our most fundamental religious and philosophical claims about human identity: that we are all the beloved children of a wholly loving and wholly worthy God. Perhaps unfortunately, progressive people don’t really talk like that anymore, so our astonishing, clear, positive, and life affirming differentiation from all-too-popular (and all-too-oppressive) fundamentalist Christian theology has been discarded and lost. I lament that loss; however, I am inspired by a provocative tangent: There is not a human thing that is not divine and no divine thing that is not human. Why? Because “theology is anthropology”. That is, what we say about God, about divinity, about Ultimacy, is and can only ever be what we humans aspire to collectively. Howard Thurman called this “the crown above our heads that we spend our entire lives trying to grow tall enough to wear”. Take that idea to infinity and you find that what you have is a sort of evolutionary roadmap — what humans can be if we ever grow up. If you want to keep with the provocative idea (and theopoetic theme), author Andy Weir wrote a story called The Egg that gives us a clever way to think about human identity, equity, and purpose. Or you might follow what the Upanishads suggest, that we are all equal in the eyes of God because thou art that.

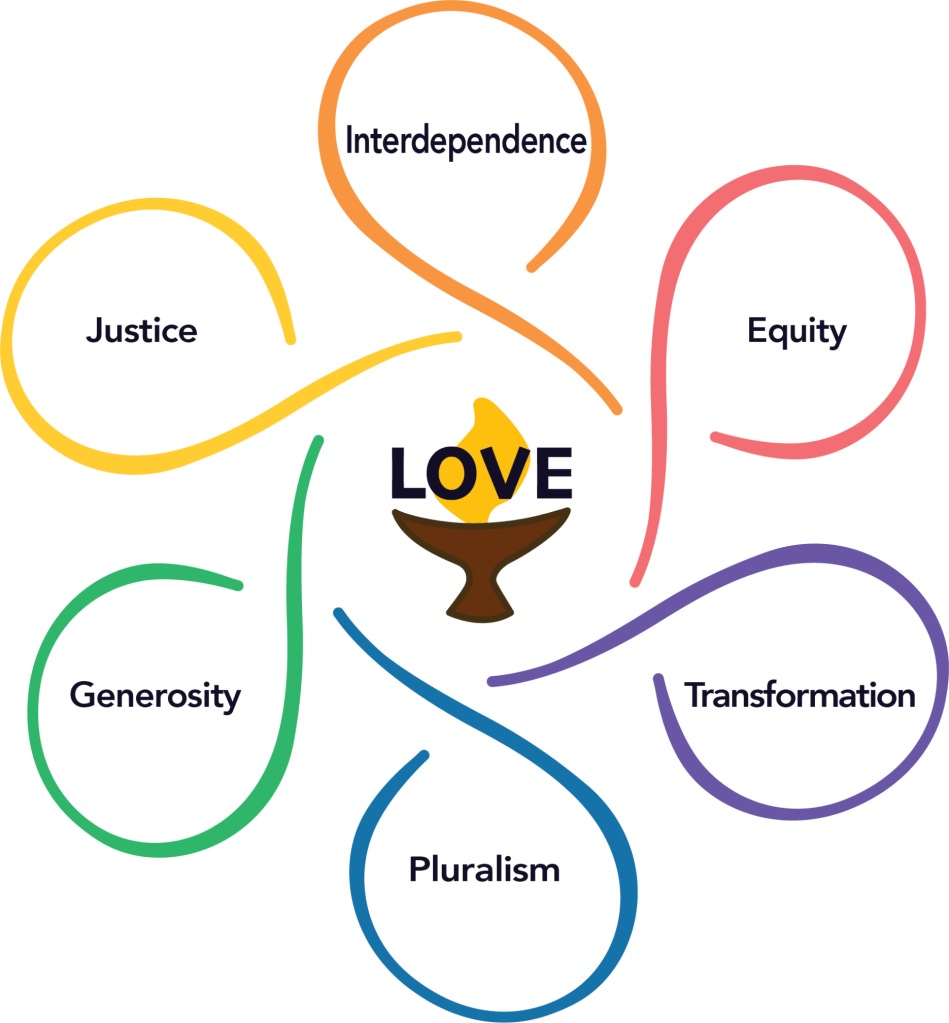

Love at the Center?

There is an additional, and central, “value” that is not listed in Six Shared Values, but does makes a rather key appearance in the “Shared Values Flower”. It’s this: Love.

This is what the revisions say about Love:

“Love is the power that holds us together and is at the center of our shared values. We are accountable to one another for doing the work of living our shared values through the spiritual discipline of Love.”

Just to be clear, this is a call out to the 8th Principle Project and the requirement for anti-racism work to include explicit language around mutual accountability. The lack of that in the language of the Principles was the reason revisions were sought. I must defer to my colleagues as to this need, the timing, and whether or not our focus on racism meant being unprepared for authoritarianism.

Centering love is blandly benign. But I’m puzzled by the complete absence of any mention of the inspirations that our very recent ancestors, drawing upon their Humanist inclinations and history, would have reflexively lifted up as timeless anchors to a modern Unitarian Universalist faith: freedom, reason, and tolerance. I’m also uncertain if our earnestness to be socially relevant sacrificed an opportunity at a grounding not bounded (and outpaced) by changing American social trends. And there’s the question if mutual accountability is truly “loving” at all. On the other hand, I will offer (with some cheek) that the recent move does land us in excellent company, since every other major religious tradition also centers love, with absolutely no exceptions.

But with the risk of being lost as a single tree in a sprawling forest, the word ‘love’ practically begs for a little deconstruction, because thanks to Hallmark and others, there is a (possibly uniquely American) problem with rebranding around it.

To be fair, the fault lies almost entirely with the English language. What our non-English-speaking ancestors would have cheerfully divided up into eight or more distinct feelings and relationships (especially if they spoke Ancient Greek), English smashes down into a single, impossibly-overburdened word. For us, love is … squishy. The word invokes weddings, fidelity, family — and while we can pretend otherwise, it also invokes cheesy seasonal greeting cards, bad country music, made-for-TV movies, and bodice-ripping novels.

Theologians in Judeo-Christian traditions have been wrestling with this challenge of “real meaning” for centuries, and that’s in part why they reached for a very old (and unfortunately bad) translation of one of the Ancient Greek words we habitually translate as “love”, the word agape. These theologians imagined this “version” of love to be a special kind of thing, something that was a transcendent, something that was selfless and pure … and extraordinarily difficult to fully grasp. Evocative as this move has been for poets, scholars now agree that what the Ancients probably meant by agape was actually far closer to what we’d now call ‘charity’. Language drift alert! But it’s true, Saint Paul and the Gospel authors were after something a bit more revolutionary than centering the King of Kings in our thoughts or fostering a change of heart among the lost and wicked. Instead, Christian love was meant to be an ethic, an aspirational way of approaching the world and the people within it. Agape, scholars say, is not about falling in love with the Power and Majesty of the Almighty, but a human life committed to compassionate action, in charitable service to each other, with the goal of making the world the heaven we were promised by scripture and the prophets. For the record, love=charity does make for some very interesting re-reading of 1 Corinthians, but that’s a sermon for another day. Today, we can just say that Joel Osteen is pretty much the opposite of what the New Testament authors had in mind.

So, to move past deconstruction and into a bit of creative reconstruction. ‘Charity’ is a fine place to start reimagining the center of any faith, if you ask me, but I suspect that most of us still love ‘love’, and giving it up will be altogether impossible, even if we mean something more than what Joel Osteen, Hallmark, or even what the ancient Fathers of the Church had in mind. And we do, I think. Just as we, in our common use, clearly and obviously mean something other than romance. The love we’re looking for is also not “tough” (as in “tough love”). And it’s not familial, or insipid or empty, and not blind, or passionate, or friendly or affectionate. And it probably should not be transcendent, because to serve us, it has to be more real than that; we need something accessible, not something only to be found at some impossible and unimaginable remove. It should be a place human beings might turn to for inspiration and support, wholeness, and hope. An idea that evokes resilience and tenderness. Something elusive but still familiar. Awful and awesome. Humble, and yes, maybe even a little crass. Soaring and, yes, maybe even a bit blasphemous. Something that recognizes an all-too-human and all-too-common gap and still speaks to both a desperate need and an aspirational hope. Something dripping with laughter and lament, longing and light. That’s the kind of root we need.

And I want to say that — if you really lean into the language, context, and intent — the love you end up with will more likely make us a tad whimsical, a tad nostalgic, maybe even a tad quiet. Because I suspect that, if we did that necessary linguistic kung-fu on the word and the intent behind it, if we dig into what we really mean by “love at the center”, then what we end up with is less charity and something far more like … home.

However wonderful, however terrible, however the experience of home was and is for each of us (and whatever it is that we mean by the idea), each of us nevertheless has a sense, an ache, a vision of what it could be. What it should be. Like the word ‘love’, ‘home’ echoes in us, sings in us, calls to us like very few other words, ideas, or ideals. Home is a hope. Maybe a memory. Potentially a place of peace, a state of joy, a nirvana where suffering can be set down. Home is where you are known and cherished. If there is a value, a single encapsulating virtue, of who we want to be, of what Love and Beloved Community really could be, it’s that. We want to be at home. In ourselves. In the cosmos. We all want a place we can call home.

And so, what if putting love at the center of faith means finally getting that? What if that’s what the love-at-the-center really is? Home. Always and forever.

I wonder. Can we ground a faith in that?